EU Drug Market: Heroin and other opioids — Production of opioids

This resource is part of EU Drug Market: Heroin and other opioids — In-depth analysis by the EMCDDA and Europol.

From poppy cultivation to heroin production

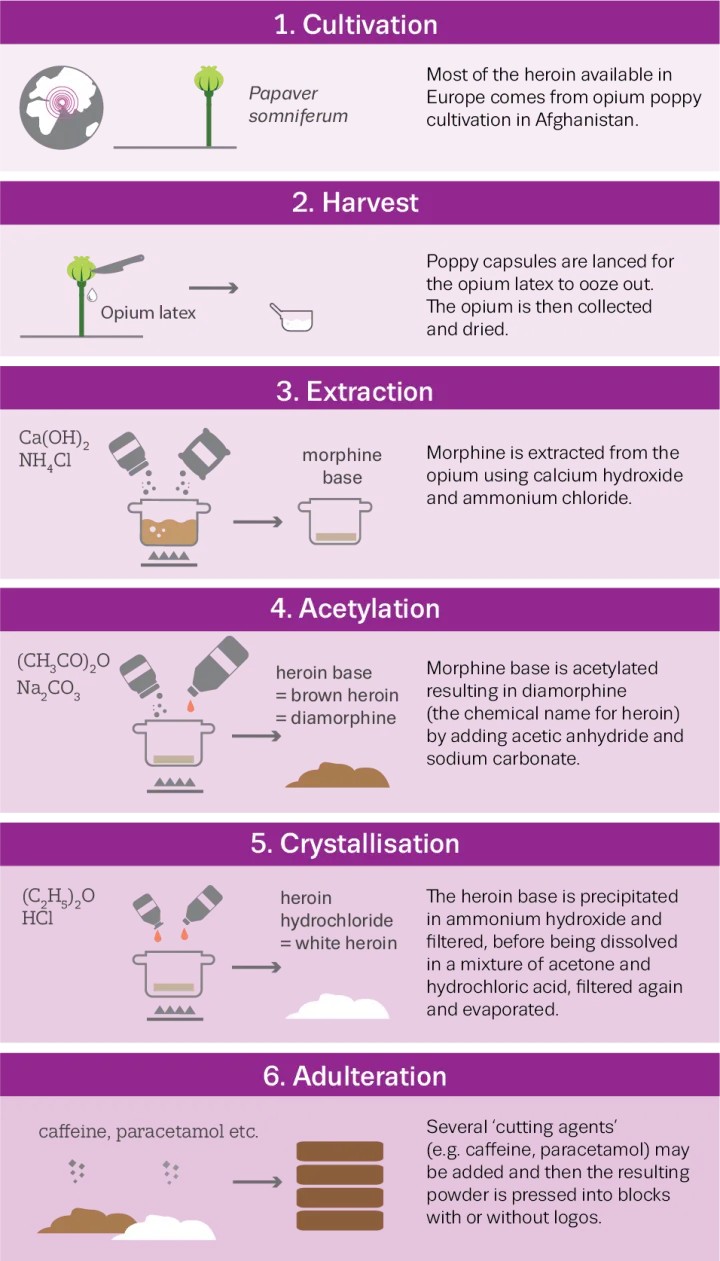

Heroin is obtained from morphine, an alkaloid that occurs naturally in opium. The process by which morphine and heroin are produced from opium harvested from poppies comprises six main steps (see Figure Overview of heroin production):

- Cultivation: Most of the heroin on the European market comes from the opium poppy Papaver somniferum, grown in Afghanistan.

- Harvest: After the poppies have bloomed, the seed capsules are incised with a knife and the opium latex contained in the capsules is allowed to coagulate and is then collected.

- Extraction: Morphine is extracted from the opium using hot water, calcium hydroxide (lime) and ammonium chloride. The resulting morphine base is air-dried.

- Acetylation: Morphine base is acetylated through the addition of acetic anhydride and sodium carbonate, resulting in heroin base.

- Crystallisation: The heroin base can be precipitated in ammonium hydroxide and filtered, before being dissolved in a mixture of acetone/ethyl ether and hydrochloric acid, filtered again and evaporated, resulting in heroin hydrochloride.

- Adulteration: Several ‘cutting agents’ (e.g. caffeine, paracetamol) may be added, with the resulting powder pressed into blocks, with or without logos.

Morphine, and therefore heroin, may also be produced by a synthetic route without the use of opium. Although these approaches have garnered much academic interest over the years, they are unlikely to be used for illicit heroin production, given the comparatively low yields and the large number of steps required (Zerell, 2005).

Poppy cultivation and opium production in Afghanistan

Until 2022 Afghanistan dominated the world’s production of opium poppies and opium (UNODC, 2022a,b; UNODC, 2023b,c). In 2022, the country had an estimated 233 000 hectares of opium poppy cultivation, a 32 % increase from 2021 (177 000 hectares) and the third largest area under cultivation since the beginning of systematic monitoring (UNODC, 2022a,b). In 2023 however, the country saw a 95 % decline to an estimated 10 800 hectares (UNODC, 2023c) (see Figure Estimated opium poppy cultivation in Afghanistan, 2013-2023).

Afghanistan accounted for 80 % of the global illicit opium production in 2022 (an estimated 6 200 tonnes out of 7 800 tonnes) (UNODC, 2023b). This was the sixth consecutive year in which production in the country exceeded 6 000 tonnes (UNODC, 2021, 2022a). In 2023, estimated production in the country fell to 333 tonnes, representing a 95 % drop (UNODC, 2023c) (see Figure Estimated opium production in Afghanistan, 2013-2023).

These figures represent opium cultivation in Afghanistan in the first cultivation season following the Taliban takeover in August 2021 (1) and the announced ban (shortly before the opium harvest began) on poppy cultivation and other drugs in April 2022 (see Section Key developments in the opiate trade in Afghanistan).

Source: UNODC, 2023c. The source data for this graphic is available in the source table on this page.

Source: UNODC, 2023c. The source data for this graphic is available in the source table on this page.

Key developments in the opiate trade in Afghanistan

The European heroin market is closely bound to the fate of the Afghan opium market as it is almost exclusively supplied with heroin from Afghanistan, via Turkish, Iranian and Pakistani organised crime networks (see Section Criminal networks operating in the heroin market). Despite the significant drop from previously consistently high opium harvests in recent years, the future of Afghanistan’s opiate trade remains uncertain as it grapples with economic instability and a humanitarian crisis. The return to power of the Taliban in August 2021 changed the country’s political trajectory, causing the international community to freeze aid programmes and evacuate the country (EMCDDA, 2022c). With widespread socioeconomic insecurity, it has become apparent that the production of opiates, a major illicit economic activity in Afghanistan, could be subject to significant change. However, the medium- and long-term trajectories of these developments remain unclear (UNODC, 2022a).

In April 2022, the Taliban announced a ban on opium poppy cultivation, raising the question of the implications this will have for Europe. The announcement of the ban has influenced the reported 248 % increase in the average national opium price in 2022 (to USD 219 per kilogram) (UNODC, 2022b). Data for 2023 shows that the prices of opium have continued to rise to an average of USD 408 per kilogram, nearly five times greater than the average price two years prior to the Taliban takeover (UNODC, 2023c).

The reduction in the area under opium cultivation includes an estimated reduction of cultivation in Helmand, the main poppy cultivating province in Afghanistan, from more than 120 000 hectares in 2022 to less than 1 000 hectares in 2023 (Mansfield, 2023). The significant drop in 2023, if sustained beyond 2023, would have major implications for the European drug market, highlighting the importance of intensifying monitoring of opium cultivation in Afghanistan (see Box Challenges and opportunities in estimating opium poppy cultivation in Afghanistan).

The long-term impact of the ban on opium cultivation is difficult to predict for a number of reasons. Importantly, the Taliban is deeply fragmented, likened to a loose conglomerate of members chasing frequently conflicting agendas and positions for power (Sharifi, 2023). It is also important to note that the Taliban’s involvement in the opiate (and other drugs) trade is complex and multifaceted and cannot be reduced to a single event or season. As such, it is unclear whether and how they will continue to enforce the ban, particularly in the context of frozen international aid programmes and the economic hardship faced by farmers in the country, which may make sustaining the ban politically difficult domestically.

How the European heroin market will be affected by the new political situation in Afghanistan is uncertain. The existence of stocks held by individuals along the opiate production chain in Afghanistan and the trafficking chain to Europe, and that it takes at least 12 months before the opium harvest appears on the European retail market as heroin, makes it too early to predict the impact on drug availability in Europe. At the moment there are no signals of heroin shortages on the European market.

If opiate production continues at the present low level, the market may take time to adapt and alternative supply sources may not be immediately accessible. It should be noted, however, that criminal networks are highly flexible. This is an important factor when analysing the Taliban’s current efforts to prohibit cultivation and production and the possible outcomes.

Nonetheless, the Taliban’s ban on opium cultivation, if it is sustained, could have a significant impact on heroin availability in Europe in the future. Experience with previous periods of reduced supply suggests that this can lead to changes in patterns of drug trafficking and use. For instance, there are historical examples of shortages in heroin supply to the European market where the use of fentanyl increased to fill the gap (Caulkins et al., 2024; Griffiths et al., 2012). In this context, the potential consequences of sustained disruption of the supply of heroin to Europe would be increased rates of polysubstance use among heroin users or an increase in the European market for synthetic opioids, including fentanyl and its derivatives, new synthetic opioids and prescription opioid medicines.

Heroin production in Afghanistan and neighbouring countries

While it is possible to estimate the global production of heroin, a number of limitations and data gaps mean that it is difficult to provide accurate estimates. It is also difficult to determine the exact locations where the drug is produced. Opium production can be more accurately quantified and located because poppies are grown in specific geographic regions and can be identified through satellite imagery coupled with knowledge of average opium yield per hectare. The average opium yield can, in turn, be used to estimate potential heroin production. For example, Afghanistan’s estimated opium production of 333 tonnes in 2023 could be converted into some 24-38 tonnes of export purity heroin (UNODC, 2023c). However, the UNODC stresses that its global heroin production estimates should be viewed as ‘best estimates’, giving an order of magnitude rather than precise measurements (UNODC, 2022a) (see Box Challenges and opportunities in estimating opium poppy cultivation in Afghanistan).

While the estimates show the potential amount of heroin that could have been manufactured from the opium produced each year, a number of factors and information gaps may have a significant impact on these estimates. These include the use of equipment and changes in production methods, but also uncertainties on key factors such as heroin laboratory efficiency, which is, in turn, affected by factors such as the expertise of the heroin ‘cooks’ and the quality of the opium paste and required chemicals.

Historically, Afghanistan is the country that has reported the largest numbers of dismantled heroin production facilities, indicating that large quantities of opium are processed into heroin in the country (UNODC, 2022a). It should be noted that Afghanistan ceased reporting on the dismantling of heroin production facilities in 2014, when 41 facilities were seized. In 2015, the country reported dismantling three facilities for the manufacture of ‘unspecified’ end products (UNODC, 2022c).

Following a period of declining morphine seizures starting in 2011, Afghanistan seized 47 tonnes in 2016, the largest quantity in the world, and seizures increased further to 63 tonnes in 2017. The reasons for the sudden and significant increase in morphine seizures in Afghanistan at that time remain unclear (EMCDDA and Europol, 2019). Since the peak in seizures in 2017, the reported amount of illicit morphine seized in Afghanistan has decreased significantly, to 240 kilograms in 2021 (see Figures Opium, morphine and heroin seizures in Afghanistan, Iran, Pakistan and Türkiye, 2017-2021).

Large opium consumer markets exist in Iran and to some extent in Pakistan. However, the very large seizures of opium and morphine in these countries indicate that some of these products may be further processed into heroin there or further along the trafficking chain (see Box Seizures of opium, morphine and heroin in Iran and Pakistan). Notably, in 2021, Europol reported that both processing and production of heroin take place in Pakistan and Iran, in addition to Afghanistan (Europol, 2021a). However, the scale of production in these countries remains unknown, and neither country has reported dismantling heroin production facilities.

Source: UNODC, 2023b. The source data for this graphic is available in the source table on this page.

Source: UNODC, 2023b. The source data for this graphic is available in the source table on this page.

Source: UNODC, 2023b. The source data for this graphic is available in the source table on this page.

Source: UNODC, 2023b. The source data for this graphic is available in the source table on this page.

Acetic anhydride: the key chemical used for the production of heroin

Acetic anhydride is the main drug precursor used in the processing of morphine into heroin and is subject to international control in accordance with the 1988 UN Convention against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances. Acetic anhydride is, however, also used in a broad range of legitimate industries, and these have grown considerably since the precursor was placed under international control. This includes use for both industrial purposes and consumer goods such as plastics, dyes and medicines. Coupled with the fact that relatively small amounts of acetic anhydride are required for illicit heroin production, these issues make preventing its diversion for illicit heroin production a challenging task.

Globally, almost 1.1 billion litres of acetic anhydride was imported by 91 countries between November 2021 and November 2022, an increase of 47 % from the previous reporting year (INCB, 2023). About 80 % of these shipments were destined for a small number of chemical companies in Europe, particularly in Belgium and the Netherlands (INCB, 2023). To put these global figures into context, according to UNODC estimates, the opium harvested in 2022 in Afghanistan would potentially require between 240 000 and 725 000 litres of acetic anhydride for conversion into between 240 and 290 tonnes of heroin. This represents roughly 0.02 -0.07 % of global licit imports of acetic anhydride between November 2021 and November 2022.

Seizures of acetic anhydride reported to the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB) have been declining substantially since 2019, a trend that continued in 2021. According to the INCB, possible reasons for this significant decrease might include a decline in the number of diversion attempts and in the subsequent trafficking of the substance, compared with the peak period of 2016 to 2018; the emergence of trafficking in acetyl chloride, a potential substitute for acetic anhydride that is not yet under international control (see Box Acetyl chloride seizures); and a shift to alternative trafficking routes (INCB, 2021a, 2023). Global seizures of acetic anhydride between 2019 and 2020 averaged 106 000 litres per year (or approximately 111 tonnes) (whereas the amount seized globally in the years 2016 to 2018 averaged 152 000 litres per year, or approximately 159 tonnes). In 2021, 58 600 litres (or approximately 62 tonnes) was seized worldwide.

Globally, the largest amount of acetic anhydride seized in 2021 was reported by Türkiye, corresponding to more than 60 % of the 58 600 litres seized worldwide in that year, confirming the country’s significance as a transit point between Europe and heroin manufacturing sites that are likely to be located in Afghanistan (INCB, 2023). Europe appears to have been the source of the majority of the acetic anhydride seized in Türkiye (25 000 out of 36 200 litres) (INCB, 2023). The acetic anhydride seized was en route to Afghanistan, Iran and northern Iraq (Republic of Türkiye, 2022).

In the EU, three countries reported four seizures of acetic anhydride in 2021, amounting to almost 6 000 litres, roughly 10 % of the global total (INCB, 2023). The Netherlands reported almost 98 % of the total amount seized (National Police of the Netherlands, 2022), with the remaining amount being reported by Belgium (2 %, 120 litres) and Latvia (less than 1 %, 1 litre). At European level, this was a slight increase from the previous year, when 5 110 litres was seized, but a significant drop from 2019, when five European countries reported a total of over 20 000 litres seized, in addition to 7 000 litres from stopped shipments in three countries (see Figures Acetic anhydride: quantity seized and quantity in stopped shipments, EU, 2018-2023 and Acetic anhydride: number of seizures and number of stopped shipments, EU, 2018-2021).

In the Netherlands, the 5 610 litres seized across two incidents in 2021 represented a sixfold increase from the 910 litres seized in 2020. In one of these cases, 2 010 litres of acetic anhydride was seized in a warehouse together with 180 litres of glacial acetic acid, 60 kilograms of sodium carbonate and a large quantity of heroin. The circumstances of this case pointed to the illicit manufacture of heroin in the country. Overall in 2021, 10 sites believed to be associated with illicit heroin manufacture were identified and dismantled in the Netherlands. In recent years, illicit heroin laboratories have also been identified in other EU Member States (see Section Opiate production in Europe: a relativtely rare occurence).

Source: EU drug precursors database. The source data for this graphic is available in the source table on this page.

Source: EU drug precursors database. The source data for this graphic is available in the source table on this page.

Information available to Europol suggests that criminal networks active in the Netherlands orchestrate the acquisition and smuggling of acetic anhydride from the EU to heroin producing countries. Other law enforcement information suggests that, in some cases, acetic anhydride from the EU has been seized alongside other drugs or swapped for heroin in transit countries, such as Türkiye (National Police of the Netherlands, 2022) (see Box Diversion and smuggling of acetic anhydride from Europe). Criminal networks take advantage of the lack of strict controls on consignments leaving the EU to smuggle acetic anhydride. In addition, limited resources and capabilities to thoroughly check cargo in transit and receiving countries may encourage criminals to smuggle the precursor along particular routes.

Acetic anhydride seizures in Afghanistan and neighbouring countries

Despite the continued cultivation of opium poppies in Afghanistan, seizures of acetic anhydride in the country have significantly declined since their peak in 2017, when 37 715 litres was seized. In 2018, the quantity seized dropped by 80 % to 7 364 litres, decreasing further to 786 litres in 2019 and to 656 litres in 2020 (INCB, 2023). However, these decreasing amounts do not reflect a diminished need for the precursor in the illicit manufacture of heroin. This is further corroborated by seizures of large amounts of acetic anhydride elsewhere, including in Europe and West Asia, believed to be destined for Afghanistan. The decrease in acetic anhydride seizures in Afghanistan is more likely to be a reflection of the security situation in the country at the time and the former Afghan government’s capacity to interdict drug and precursor shipments (Felbab-Brown, 2020).

Seizures of acetic anhydride have also continued to be made in countries neighbouring Afghanistan, such as Iran and Pakistan, and in the UAE. In 2020, Iran reported seizing a shipment of 13 900 litres of acetic anhydride, misdeclared as paint, in the seaport of Bandar Abbas. The shipment was destined for Afghanistan and shipped from the UAE (INCB, 2021b). In 2020, Pakistan reported three seizures of acetic anhydride amounting to 5 130 litres. The largest of these took place in the port of Karachi and involved 2 972 litres, allegedly originating from China (INCB, 2021b).

Opiate production in Europe: a relatively rare occurrence

Production of heroin is uncommon in Europe, although the final step of the production process – the acetylation of morphine into heroin – has been reported in Germany, the Netherlands and France. Most of the facilities associated with illicit heroin production reported in the EU between 2018 and 2021 were sites for processing, i.e. cutting and packaging, or waste dump sites (see Table Facilities associated with heroin production in Europe). At cutting and packaging facilities, heroin is adulterated to increase the volume of the drug and packaged for onward distribution. For example, Dutch criminal groups appear to specialise in the preparation of heroin cutting mixtures for these types of facilities (typically using caffeine and paracetamol) (see Section Heroin adulteration and Box Dutch criminal networks specialise in heroin cutting mixtures). Importantly, a facility associated with heroin production may be involved in several of these activities simultaneously (see Table Facilities associated with heroin production in Europe).

| Type | Activities |

|---|---|

|

Cutting and packaging facilities |

Adulterating heroin, packaging for onward distribution |

|

Production or processing sites |

Acetylation of morphine into heroin Extraction of morphine from opium |

|

Waste dump sites |

Preparing and disposing of toxic waste from processing or adulterating heroin |

|

Storage sites |

Storing precursors or other chemicals, equipment, heroin or intermediary products |

|

Extraction sites |

Extraction of heroin from concealment materials |

At least 15 sites associated with illicit heroin production were dismantled in the EU between 2018 and 2021. Ten of those sites were dismantled in the Netherlands in 2021, clustered around Alkmaar, The Hague and Rotterdam, with confirmed heroin production at three of the sites. Preliminary data related to two laboratories dismantled in The Hague region indicate that heroin production or processing continued in the Netherlands in 2022 (Politie, 2022). While there is limited information about the heroin production facilities identified in the EU, including their production capacities and the source of the morphine used in the process, the evidence indicates that heroin production in the EU persists, albeit at a low level, and is made possible by the ease with which acetic anhydride can be diverted from legitimate suppliers in Europe.

Heroin production or processing has also been noted in countries bordering the EU. For example, Albanian law enforcement authorities dismantled a heroin production laboratory in 2018 (EMCDDA, 2022a; UNODC, 2022d). In 2022, Kosovo (2) reported dismantling two facilities set up for the processing and packaging of heroin. The facilities were operated by Turkish suspects working with local criminals (EMCDDA, 2022a).

Seizures of morphine, possibly intended for processing into heroin, have also been noted in several EU countries. In 2021, Spain reported the seizure of 3.4 kilograms of morphine, while Austria and Sweden each reported seizing over 6 000 tablets/capsules of morphine. In addition, seizures of opium have been noted in several EU countries. In 2021, Bulgaria reported seizing 27 kilograms of opium, while Spain and Sweden reported seizing 15.6 kilograms and 12.5 kilograms respectively. Türkiye reported seizing 976 kilograms of opium in 2021, some of which was destined for western European countries. The opium available in Europe could be used for heroin production or by individual consumers where demand exists.

In addition to the production of heroin from imported morphine or opium, since 2018 Czechia has reported dismantling three small-scale heroin production facilities that were using poppy straw or morphine extracted from medicines. The production of a range of other opiate preparations, often made from poppies or ‘poppy straw’ (the dried stalks, leaves and seed capsules of opium poppies, which contain residual opium alkaloids) also continues in some European countries.

Environmental impact of heroin production

The illicit production of all plant-based and synthetic drugs entails a range of environmental harms. With regard to heroin, most of the environmental impacts and harms relate to the cultivation of opium poppies that takes place outside the EU. Field preparation requires agricultural inputs, including pesticides and irrigation, leading to energy and land use, to water, soil and air pollution, and to emissions of biogenic volatile organic compounds (UNODC, 2022a). The dumping of waste materials from production threatens fragile ecosystems, and the extensive cultivation of these crops leads to a range of environmental harms, including soil erosion. Specifically, in Afghanistan, the use of pesticides and of solar- or fuel-powered irrigation methods has led to soil depletion and reduced groundwater levels (Mansfield, 2018). While these harms may have no direct impact on the EU, they could have indirect effects through migration, destabilisation and climate change (EMCDDA and Europol, 2019).

In the EU, the identification of laboratories associated with heroin production, albeit in small numbers, indicates more direct damage pathways in terms of the dumping of toxic waste. From 2018 to 2021, at least 15 sites associated with the production of heroin were identified and dismantled (see Section Opiate production in Europe: a relatively rare occurrence). While the number of reported dumping sites related to heroin production is low compared to the number of dumping sites related to synthetic drug production, the use of precursors, water and electricity may cause direct harms to the environment in the EU.

Synthetic opioid production in Europe: a marginal phenomenon

The market for synthetic opioids has been growing in Europe, and it appears that most illegally produced synthetic opioids distributed in the EU originate from non-EU countries. Depending on the destination country and the mode of distribution, the three main source countries for synthetic opioids available on the European drug market are believed to be China, India and, to a lesser extent, Russia.

Some production of synthetic opioids, including new synthetic opioids, may occasionally occur in the EU, although currently this would appear to be marginal compared with the manufacturing of other illicit drugs. Laboratories carrying out the full production cycle of synthetic opioids are rarely found, and there does not appear to be any widespread or sustained illicit production of these substances. However, because these substances are very potent (often orders of magnitude greater than morphine), even a small illicit laboratory could produce sufficient material to satisfy national or even EU demand.

France and Estonia each reported dismantling a small-scale laboratory for the production of fentanyl in 2018 and 2019, respectively (UNODC, 2022c). In May 2023, the Latvian police seized a large quantity of fentanyl (approximately 5 kilograms) together with fentanyl precursors, which suggests that fentanyl production might have taken place in the country (Valsts policija, 2023). Overall, with a few possible exceptions in the Baltic countries and in countries bordering the EU, there is no strong evidence of significant fentanyl production currently occurring elsewhere in the EU. Nonetheless, this situation may change rapidly should market conditions become favourable in the future (see Box Factors that could increase the threat of synthetic opioid production in Europe).

Between 2016 and 2020, almost 85 kilograms of fentanyl precursors – including the precursor 4-anilino-N-phenethylpiperidine (ANPP) and the alternative chemical N-phenethyl-4-piperidone (NPP) – were seized in three EU Member States (Belgium, Estonia and France). While no fentanyl production sites have been identified in the Netherlands, seizures of fentanyl have been reported there (Openbaar Ministerie, 2020, 2021a). Furthermore, in 2020, the National Police of the Netherlands reported the seizure of chemicals used in the production of fentanyl, along with the final product, indicating that fentanyl production may take place in the country (see Box Signals of possible fentanyl production in the Netherlands).

Cutting and packaging facilities for synthetic opioids are more commonly detected in the EU than laboratories producing these substances. However, reporting rarely differentiates between the two. In 2020, Latvia reported detecting and dismantling one small-scale site for the manufacture or packaging of the benzimidazole isotonitazene (UNODC, 2022c).

The illicit production of methadone is also known to take place in the northeast of Europe. For example, a small-scale illicit laboratory producing methadone using precursors diverted from the legal market was dismantled in Latvia in 2020. This followed the detection of a larger illicit methadone laboratory in Latvia in 2017 (EMCDDA and Europol, 2019). Ukraine reported dismantling three medium-scale methadone production laboratories in 2020 and two medium- and one small-scale laboratories in 2019 (UNODC, 2022c).

(1) In some provinces in Afghanistan, opium poppies are harvested twice in a year. This estimate considers only the main season, as the second harvest is marginal in comparison, based on the evidence available (UNODC, 2022b).

(2) This designation is without prejudice to positions on status, and is in line with UNSCR 1244/1999 and the ICJ Opinion on the Kosovo Declaration of Independence.

Source data

| Year | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hectares | 209000 | 224000 | 183000 | 201000 | 328000 | 263000 | 163000 | 224000 | 177000 | 233000 | 10800 |

| Year | Tonnes |

|---|---|

| 2013 | 5500 |

| 2014 | 6400 |

| 2015 | 3300 |

| 2016 | 4800 |

| 2017 | 9000 |

| 2018 | 6400 |

| 2019 | 6400 |

| 2020 | 6300 |

| 2021 | 6800 |

| 2022 | 6200 |

| 2023 | 333 |

| Year | Heroin (tonnes) | Morphine (tonnes) | Opium (tonnes) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 2.3 | 63.3 | 7.31 |

| 2018 | 5.1 | 18 | 27 |

| 2019 | 4 | 17.6 | 24 |

| 2020 | 3.1 | 0.1 | 6.8 |

| 2021 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 5.4 |

| Year | Heroin (tonnes) | Morphine (tonnes) | Opium (tonnes) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 24.5 | 7.3 | 40 |

| 2018 | 5.7 | 4 | 19 |

| 2019 | 8 | 6.3 | 30 |

| 2020 | 28 | 17 | 47 |

| 2021 | 9.6 | 10.1 | 35.6 |

| Year | Heroin (tonnes) | Morphine (tonnes) | Opium (tonnes) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 23.8 | 15.1 | 630.6 |

| 2018 | 25 | 21 | 644 |

| 2019 | 17 | 18.2 | 656 |

| 2020 | 31 | 27 | 916 |

| 2021 | 25.5 | 36.6 | 834.9 |

| Year | Heroin (tonnes) | Morphine (tonnes) | Opium (tonnes) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 17.8 | 0 | 0.934 |

| 2018 | 19 | 0.4 | 0.7 |

| 2019 | 20 | 0 | 1.3 |

| 2020 | 14 | 0 | 0.8 |

| 2021 | 22.2 | 0 | 0.9 |

| Year | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantity seized | 15667 | 20038 | 5109 | 5731 |

| Quantity in stopped shipments | 8888 | 6977 | 0 | 0 |

| Year | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of seizures | 12 | 9 | 7 | 4 |

| Number of stopped shipments | 8 | 11 | 1 | 0 |

References

Consult the list of references used in this module.